We publish in full the corporate tone of voice guide draft that can be used as example for your brand’s own guide. We regularly review it, adding to it.

We hope it helps you in defining your brand’s writing guidelines, as it helped many companies before you!

[Your Company’s Name]

Tone of Voice Guide

date/month/year

Powered by Writitude

Feel free to download the guide

1. Why are you reading this?

1.1. The purpose of ToV

Tone of voice guides, or ToVs, as they are commonly known, are designed with one main purpose in mind — to ensure that customers have great experience with a company through time, on all subjects and across all platforms. To achieve this goal, ToV of a company or brand needs to be:

• unique so that it differentiates a company from its competitors (the same function as visual identity);

• consistent so it does not create disruptions and is predictable from the viewpoint of a customer. This is a reasonable goal for any company, big or small.

1.2. The challenges solved with this document

Yet often even well-meaning teams fail at their corporate ToVs. There are three main challenges to establishing consistent communication:

• Formalization

Each company already does have a ToV, even if they have never thought about it. It occurs spontaneously from company’s culture and personal traits of people, doing the communication.

The problem is, if the rules are not set, they tend to be vague, can be disputed and change easily.

This is why formalization of a tone of voice in the form of detailed guidelines is the best way to ensure that the most important principles (and their practical manifestations!) are clear to everybody.

• Different registers/genres

As company’s communication serves different purposes (such as sales, customer support, image-building etc.) the style and tone of texts company uses also tends to vary extensively.

It is typical of companies to speak in one voice when they are trying to sell a product, and in a completely different one — when troubleshooting issues or dealing with customer complaints.

Setting a minimum subsistence level of basic rules that need to be followed at all times, helps tackle the natural human tendency to switch tone from friendly to defensive when faced with challenging situations.

• Human factor

If a company has more than one person doing the communication, in the absence of clearly defined rules it will inevitably vary.

People differ not only in terms of their extraversion or agreeableness, they also have surprisingly varied understanding of meanings and connotations of different words or phrases.

Another level of human factor challenge occurs when communication/marketing specialists change, and they eventually do so in every company.

If the only agreement that binds company’s communication is in the form of mutual understanding of certain people, there is a risk of disruptions when new people are hired. It also makes integrating a new employee slower and costlier as unwritten rules are hard to convey.

A good ToV guide solves all of these issues by providing a clear set of rules that can be followed by all communicators across subjects and channels for as long as they fit their company’s identity.

The following guidelines are designed to provide not only principles, but a detailed advice on their implementation in real-life texts.

1.3. How to use this template

From abstract to particular It is as important to understand the rationale behind a ToV as it is to train yourself to solve the practicalities of com munication. That is why this guide starts with the abstract (the conceptual rules) and goes on to explain the particularities.

The first part grounds the rules in argumentation, while the second demonstrates how they work on three different levels of language: content, style and grammar.

The last part of the document contains a list of control questions that help to understand, if a particular piece of text (an email offer, a Facebook post or a script for cold-calling) is consistent with the ToV of [your Company].

Refer to this guide whenever:

• you have to write a new piece of text in the name of [your Company]; • you have to evaluate the relevance of a text template written some time ago; • you have to explain to a new colleague “how we do things here at [your Company]”.

It is also a good idea to print out the control questions and have them at hand for a quick check-up of texts written by yourself or your colleagues.

2. Who are you talking to?

A corporate tone of voice development is rooted in understanding your audience, its needs and identities. In order for [your Company] to communicate successfully, you need to define personas within the target audience, to make it easier to identify the audience segments you want to reach.

Neither you nor your team members are the target for the texts you’re creating, so don’t judge them by your own standards. Always keep in mind your target audience personas whenever you’re writing a text to a particular market segment.

2.1. Audience description

(Describe your audience. Are your buying audience, your stakeholders and your communications audience one and the same? Explain the difference.)

2.2. Target audience personas

Every group which [your Company] communicates with is described by a target audience persona. Each persona is defined by parameters that are relevant to [your Company] and the particularities of the buying process that person goes through.

[Target audience persona 1]

(Describe your audience persona 1. Think of a name, age, social status and whether they have kids or not. What is their workplace, lifestyle and hobbies?

Try describing in detail the brands of household items that they use. Describe their habits and state of affairs that relate to [your Company’s] service or product. What is their main reason for choosing [your Company’s] service or product?)

[Target audience persona 2] (Description) [Target audience persona 3] (Description) [Target audience persona X] (Description)

A tip!

Don’t make things up. Consider talking to your clients and other audience representatives for creating a really insightful audience persona. Interviews and focus groups would also be very beneficial (and actually are a must).

Also, keep it simple.

Out of a myriad of possible characteristics, choose those that are relevant for your specific case — sometimes it will matter if your customers drive a car or own a cat, sometimes — not so much.

3. [Your Company’s] tone of voice main pillars

A corporate ToV is rooted in the company’s philosophy — its mission, vision, values, the stories it has, its team and its product, and of course — its particular relationship with its audience.

The ToV of [your Company] is based not only on [your Company] as a company or [your Company] as a product or service, but also a process that evolves around [your Company] — a process that (describe the process that evolves around your product or service from your customer’s point of view and benefits).

It is important to understand that the descriptions of a company’s mission, vision and values are not communicated to the customer directly. They should not be used as talking points.

Saying you’re a sustainable company doesn’t help much — show it in the particulars! Yet, these fundamentals serve an important function in defining your public communication by setting its foundation.

3.1. [Your Company’s] identity stories, statements, and values

Brand purpose (Write here in 1-2 sentences — what’s the reason your business exists beyond making money — the WHY of your business) (Longer description — go deeper into what you meant by that, be more specific)

Vision (Write here in 1-2 sentences — where you want your brand or business to be in the future) (Longer description — go deeper into what you meant by that, be more specific)

Mission (Write here in 1-2 sentences — what (think — specific tactics around your product or service, operations, strategy or communications) should you do in order to get there?) (Longer description — go deeper into what you meant by that, be more specific)

Our values [Value 1] (Description — go deeper into why this value is important and how it is reflected in what you do) [Value 2] (Description — go deeper into why this value is important and how it is reflected in what you do) [Value X] (Description — go deeper into why this value is important and how it is reflected in what you do)

3.2. [Your Company’s] business story

Subtitle 1 Ideas are born in so many different ways. Sometimes it’s a long-awaited discovery, sometimes — a pure accident (just ask Newton!). Our idea was born out of a [your Company’s inception story]. This is how our company started. Subtitle 2 (text) Subtitle X (text)

3.3. [Your Company’s] customer story

(Describe the usual perception of your product or service that you’ve changed or are about to change) First, there is [challenge 1] Second, [challenge 2] Until one day I saw / met [Your Company or product] In other words, (Describe why your customers love you)

3.4. [Your Founders’] personal story

Subtitle 1 (text) Subtitle 2 (text) Subtitle X (text)

3.5. [Your Company’s] product/ service story

Subtitle 1 (text) Subtitle 2 (text) Subtitle X (text)

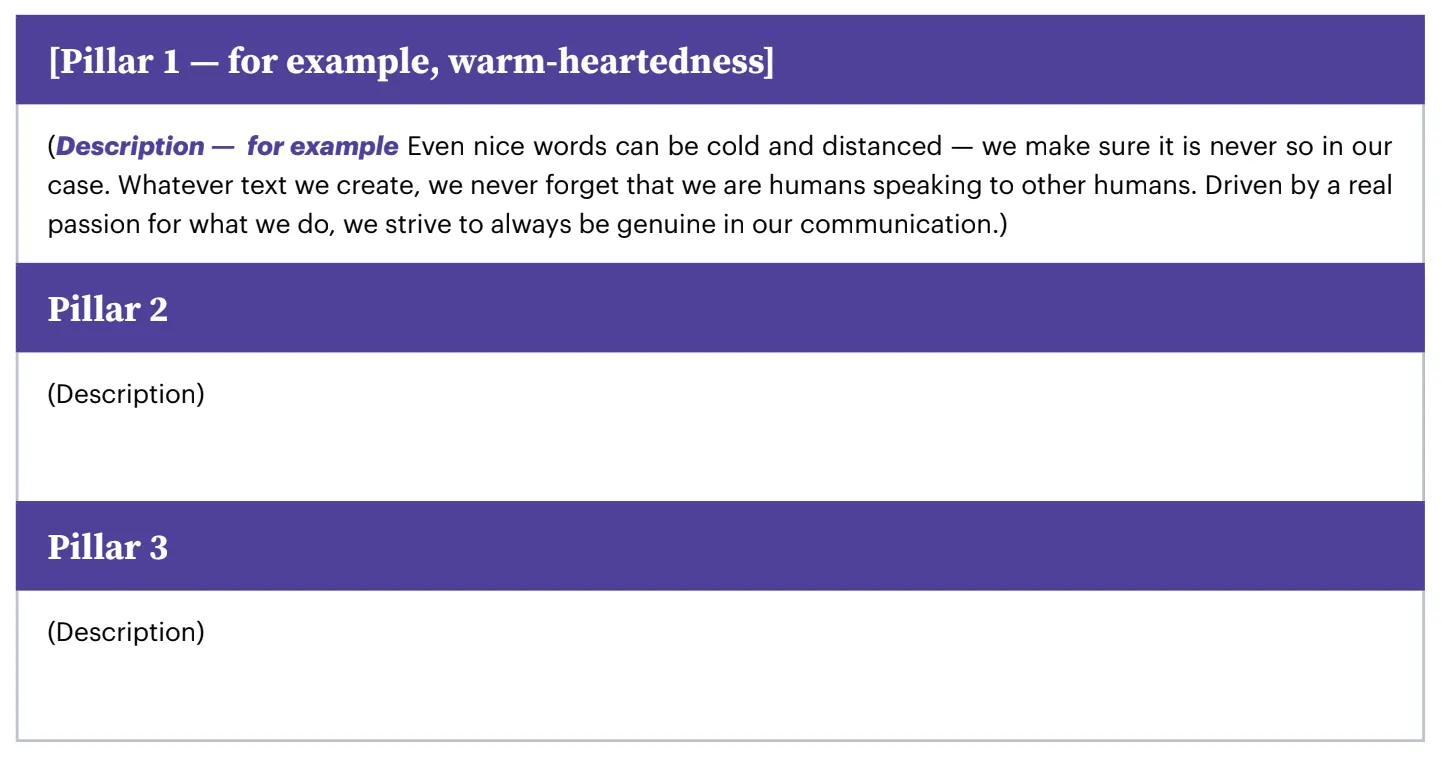

3.6. Tone of voice pillars

The three main pillars (or foundations, or rules) that guide all communication by [your Company] and its team are based on [your Company’s] identity, its stories and its values.

Taken separately, none of these pillars is, strictly speaking, unique — these arguments inform communication practic es in many companies.

The same as with personality traits — what makes a person unique, is not isolated character istics, but a particular combination and interpretation of them that persists over time and across different channels.

That is why it is important to regard these pillars as synergetic — a unique [your Company’s] tone of voice occurs when ALL of them are present in communication.

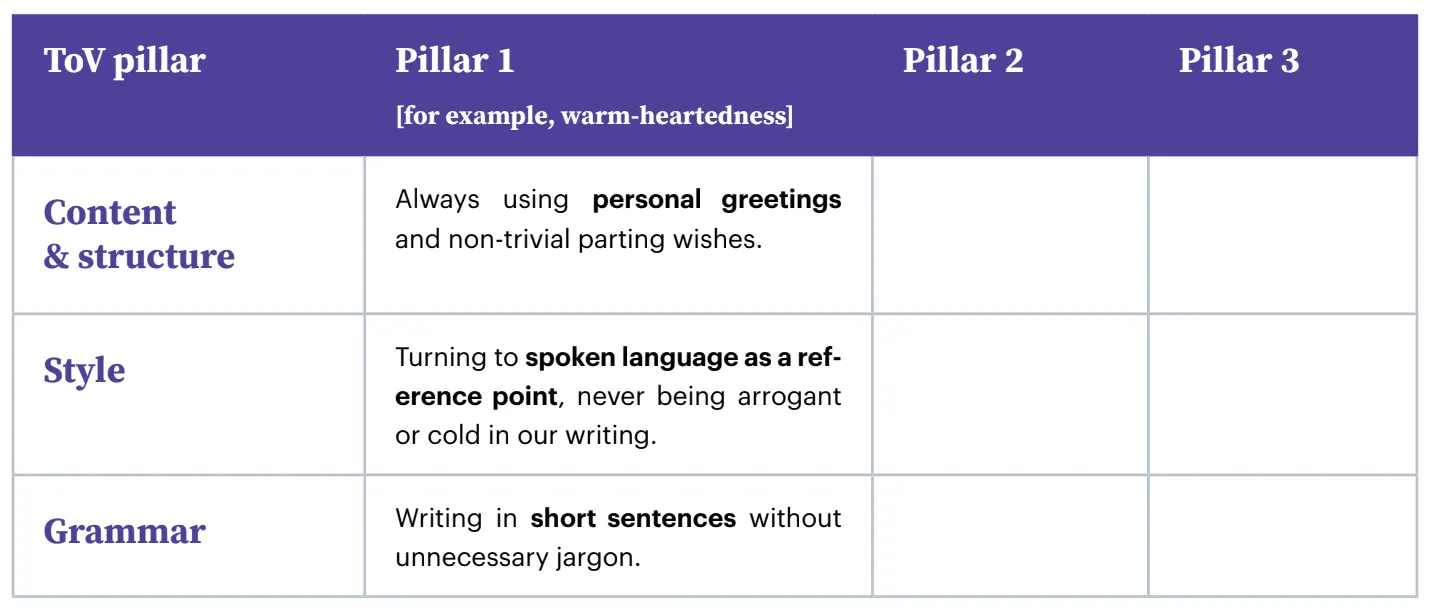

3.7. Levels of meaning

To understand the real-life manifestation of these principles, let’s slice them into three levels. In language, tone and emotion can be conveyed by making certain decisions about the content and structure of a text, by stylistic choices of certain techniques (and conscious avoidance of others), as well as on the level of grammar (words, phrasing and sentences).

This is how warm-heartedness, Pillar 2 and Pillar 3 play out on levels of meaning:

These rules set out the field where optimal communication occurs. In the next section, you’ll find detailed explanations and analysis of examples, both good and bad, that will help you to master [your Company’s] tone of voice.

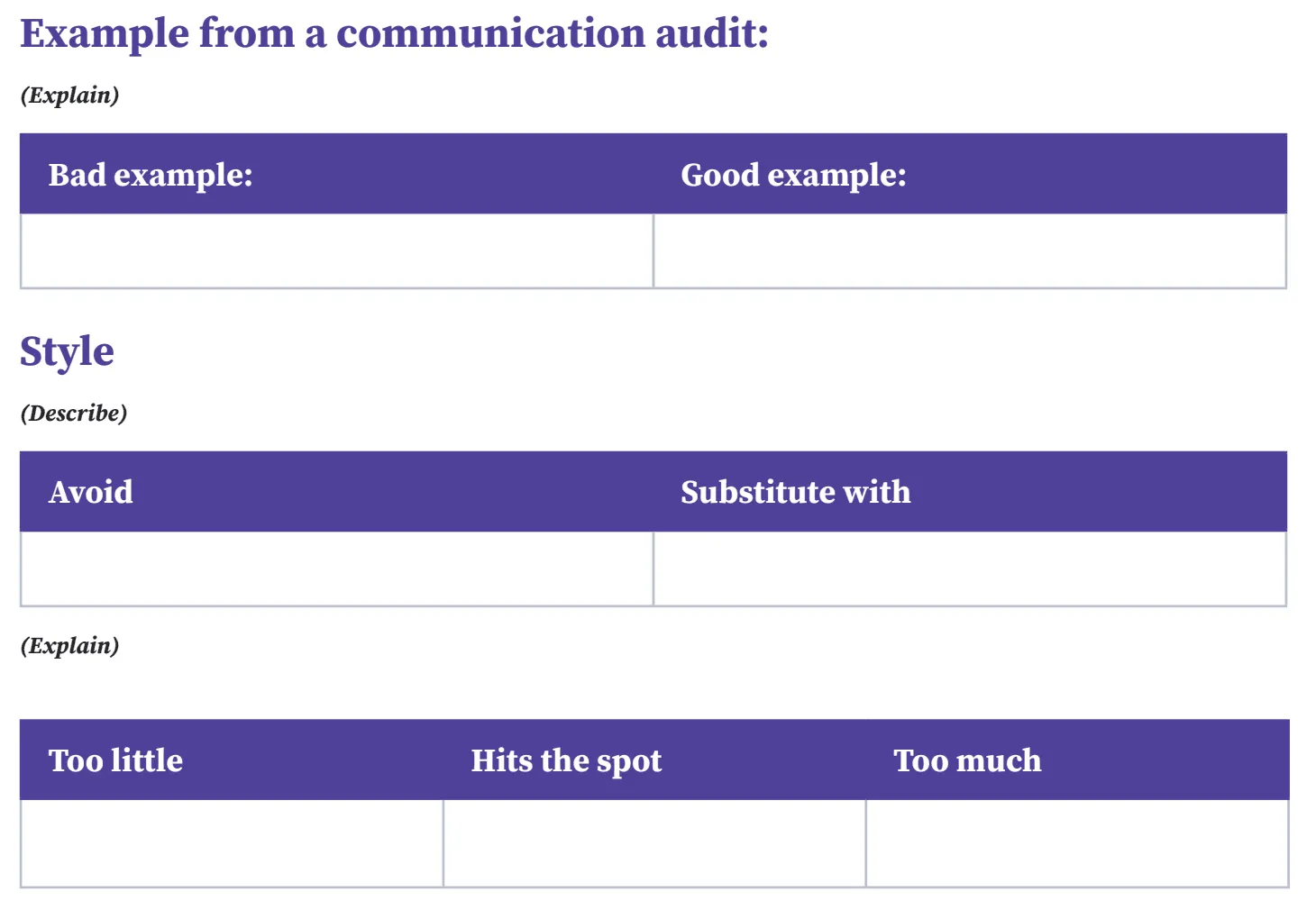

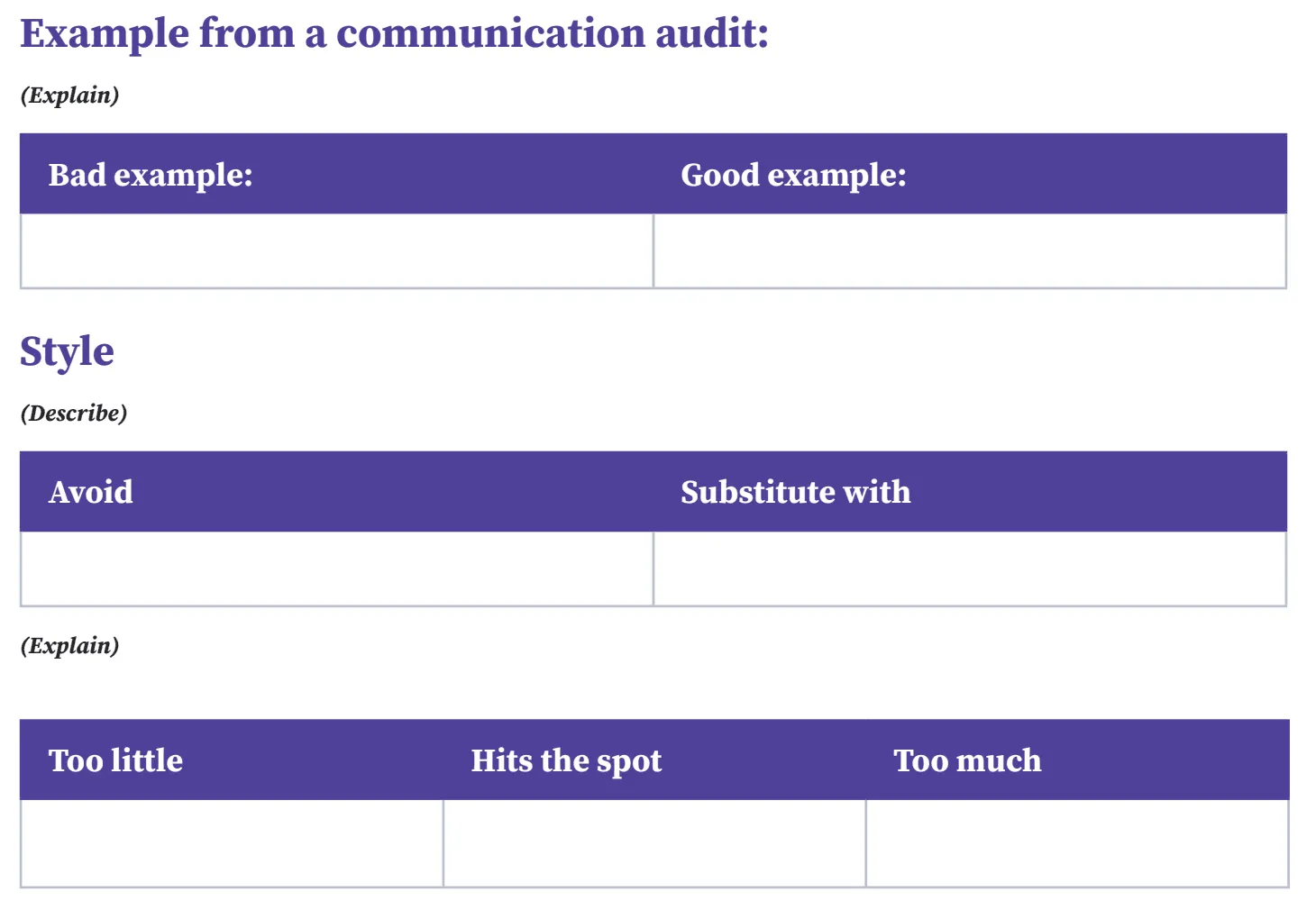

4. Making it fit – calibration of ToV

Each of the communication pillars, laid out in Part 3 of these guidelines, can be implemented in three levels of language. They can also go wrong in more than one way — putting too much [for example, warm-heartedness] into a text can be as harmful as providing too little of it.

That is why this sections focuses on meticulous balancing of ToV principles and exhaustive analysis of good and bad practices.

4.1. [Pillar 1 — for example, warm-heartedness]

(Explain) Even nice words can be cold and distanced — we make sure it is never so in our case.

Whatever text we create, we never forget that we are humans speaking to other humans. Driven by a real passion for what we do, we always strive to be genuine in our communication.

Content and structure (Explain in context)

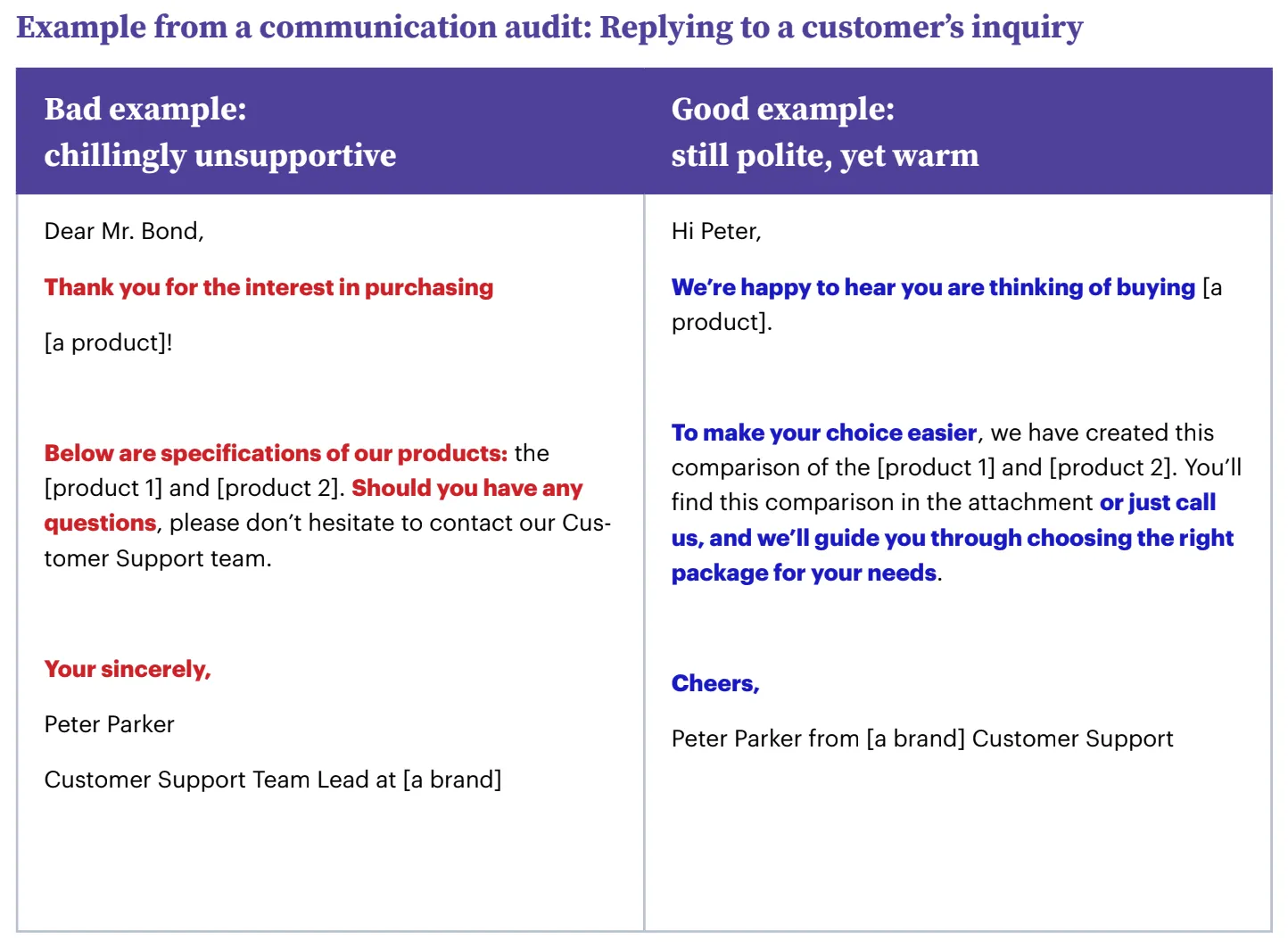

The risk of sounding cold is the highest in writing and the lowest — in presence of a communication partner.

Written communication is distanced by definition, it also lacks non-verbal clues (such as intonation, physical distance between speakers, posture, gestures, eye contact), that would make up a large portion of understanding the attitude of a communication partner in person.

As emails are devoid of possibilities to communicate sympathy in a non-verbal way, we have to put extra attention into conveying it verbally.

Lack of non-verbal signals is the reason why corporate written communication often reads cold without any intention of doing so.

Coldness also appears as a side-effect of companies trying to be polite and being afraid of offending people.

Whilst staying on the safe and formal side is a good choice for a bank or a government institution, it is unsuitable for a brand like [a brand]. So how do we sound warm and still be polite?

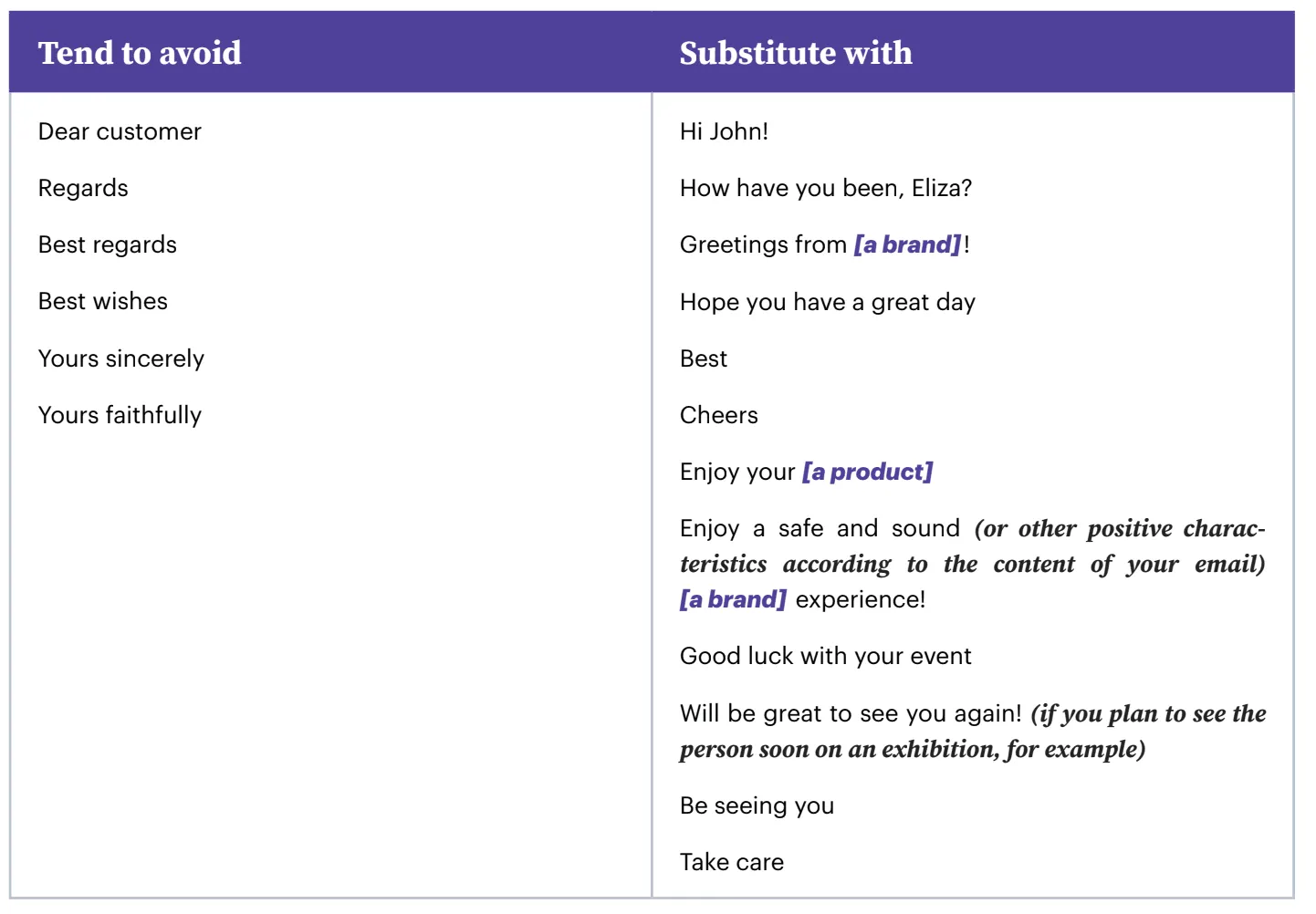

(Explain in a new context) Greetings and endings are one of the very few places in an email, where emotion and attitude can be expressed directly. With rare exception of Japan, Korea, China and several others Asian countries, in the majority of cultures we rarely risk offending someone by choosing a less formal greeting, especially, if they know that it is not a personal choice of an employee, but a part of brand’s communication style (which they are probably already familiar with at the point of initiating a direct communication via email).

The same applies to endings — as they don’t carry any content, their only function is to convey attitude. By choosing a standardized ending (such as “Best regards”, “Regards”, “Best wishes” etc.) we communicate unattentiveness. We send a signal of standardized treatment of all customers, of choosing not to make an effort, which also becomes a contradiction in the context of “count-on-me attitude”.

(Explain in a new context)

Manifestations of gratitude also need to be de-formalized. At [a brand] we don’t use standardized corporate ways of thanking our customers (such as “Thanks for reaching out”, “Thanks for your inquiry” etc.) because that comes across as insincere. Instead, we go for phrases that we would use when thanking someone in spoken language. This will also bring a wider set of variations into our communication, making gratitude more carefully tailored to the exact situation.

Style

(Explain) The opposite of warm-heartedness is cold and distanced communication, speaking from above, arrogant and we-know-it-better attitude that makes a recipient feel small and incompetent. This style of writing is often used deliberately by financial institutions because they believe it delivers better compliance with the rules. In case of [a brand] this would be absolutely unacceptable, yet distanced and arrogant communication also often appears involuntary.

(Set a reference) The best way to ensure against formalism and arrogance is make spoken communication our reference point instead or navigating with standards of written communication in mind.

Here are the main stylistic differences between spoken and written language:

• Written language is organized by punctuation, while spoken language — by rhythm, speed and tone;

• Speech rarely refers to itself, while in written form expressions such as “as mentioned above” are fairly common;

• Colloquial words and informal expressions are more often used in spoken form, while specific and precise terminology — in writing.

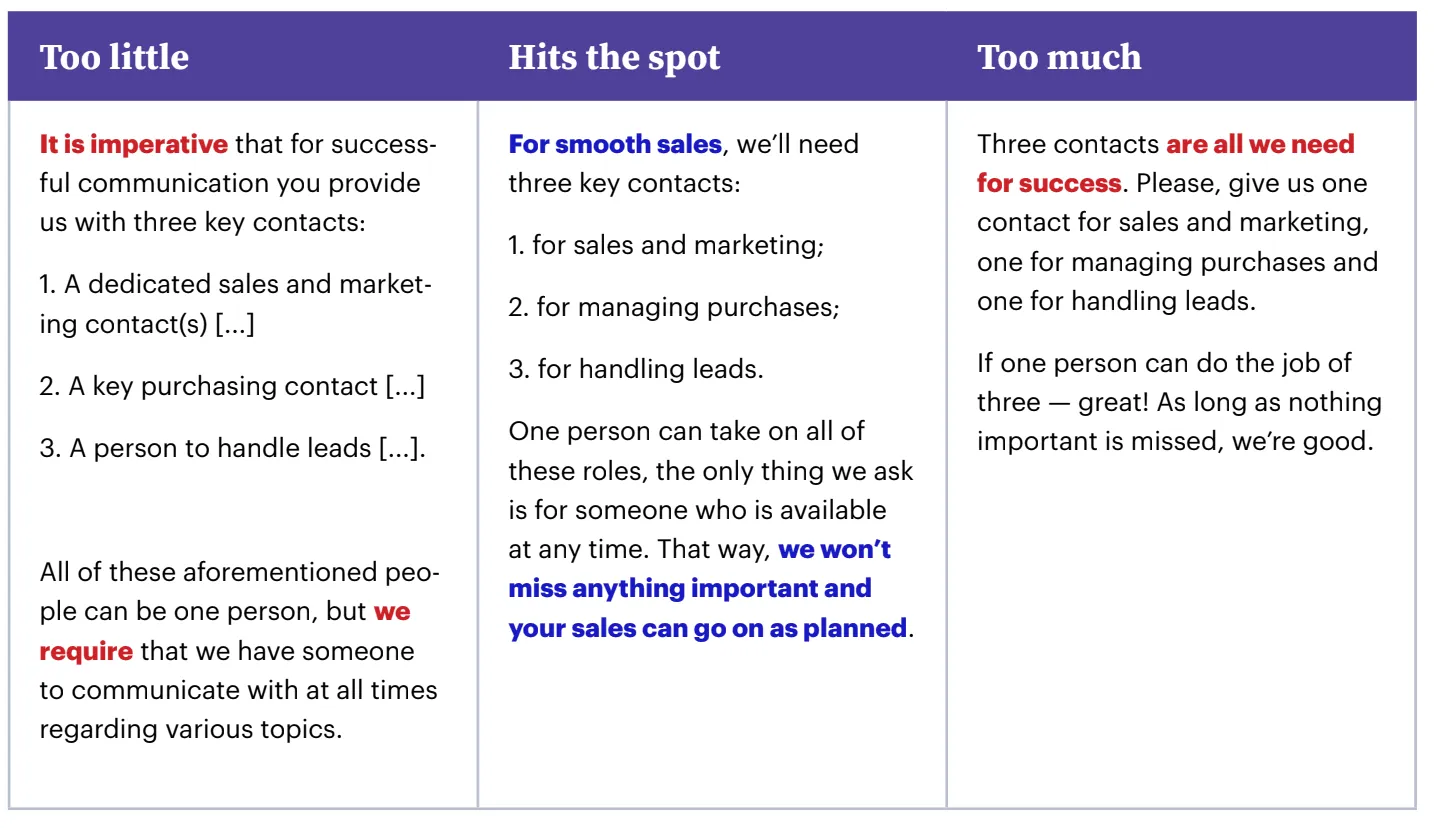

(Explain what’s wrong) The use of authoritarian language (“imperative”, “require”), as well as expressions and words forms used only in written language (“contact(s)”, “aforementioned people”) is what makes the first example sound cold. A few changes in the second example make it sound considerably warmer, while still keeping it in the domain of polite corporate communication:

• Explaining the reason for requiring contacts in the beginning and the end of the text (and not ordering something without explanation);

• Personalizing the request (“we’ll need” instead of abstract “it is imperative”);

• Getting rid of written-only “contact(s)” as unnecessary — the text already mentions three persons in total;

• Changing the balance for humanizing by cutting on the use of “contacts” in the list as it is already mentioned in the beginning.

The “Hits the spot” example also uses shorter sentences and contractions, typical of spoken, rather than written language. More on that — in the next section. At the same time the third example makes overuse of various shortcuts by using numbers instead of words multiple times.

It also steps over the line in simplifying the matter — “do the job” does not explain what it means exactly while “nothing important is missed out” and “we’re good” is too abstract.

Grammar

(Explain) In grammar the main differences between spoken and written language are these:

• Spoken language is imperfect — it usually contains unfinished sentences, repetitions etc.;

• Sentences in spoken language tend to be considerably shorter and less complex, while written language can handle many subordinate clauses;

• Spoken language is economical — in direct interactions people opt for contractions that are faster and easier to pronounce (“I’m” instead of “I am”);

• Personal pronouns are used much more frequently in spoken language. While some of these characteristics mark sharp differences between spoken and written forms of language and would be inappropriate when used in other domain (such as unfinished sentences in writing), most are softer differences that can be applied to written texts to make them sound livelier and less formal.

And as we strive to always sound genuine, these latter properties of spoken language (shortness, economy, use of personal pronouns) are exactly what we aim at. Yet they still need to be carefully calibrated.

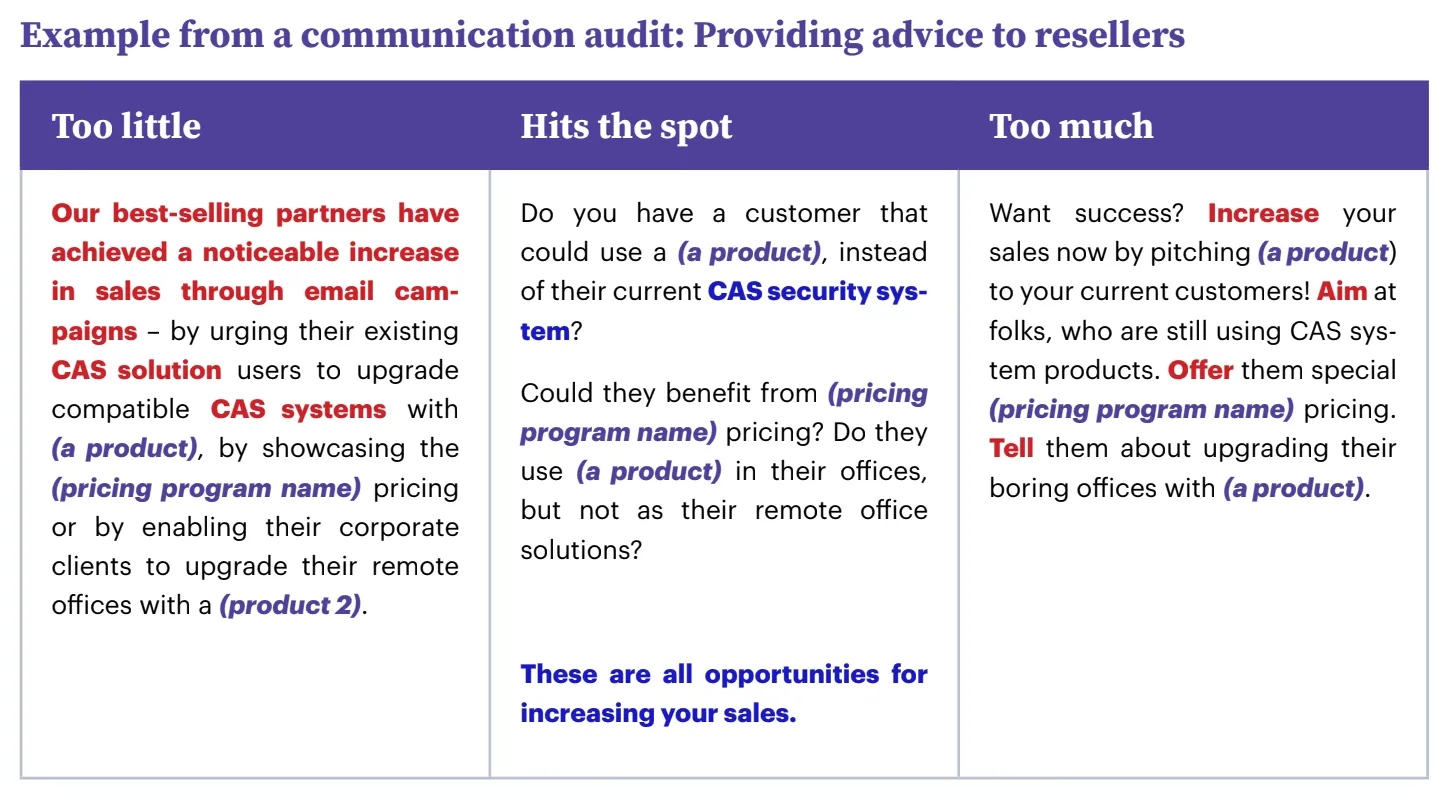

(Explain the difference in your examples) While the first example features one extra-long sentence, the third example consists of five super-short sentences. The second (Hit the spot) example offers a midway between the two extremes by using 4 sentences, some of them in the form of a question with the average of 11.5 words in each. This makes the first example sound rather heavy (and clearly bound to its written form) and the third example — as too aggressive, because too short sentences resemble shouts.

Another difference is the form of sentences — the first example offers a detached description of possibilities, while the re-written examples go for direct address. Yet the third example takes it too far by using order-like phrasing repeatedly (“increase”, “aim”, “offer”, “tell”).

The use of terminology should also be carefully calibrated not to be too specific or too informal. While “CAS systems” (specific and formal) is an insider’s way of communication, “CAS security system” makes the term more widely comprehensible by mentioning the security, and still retains the informal approach.

4.2. Pillar 2

(Describe) Content & structure

(Explain in context)

Grammar (Describe)

4.3. Pillar 3

(Describe)

Content & structure (Explain in context)

Grammar (Describe)

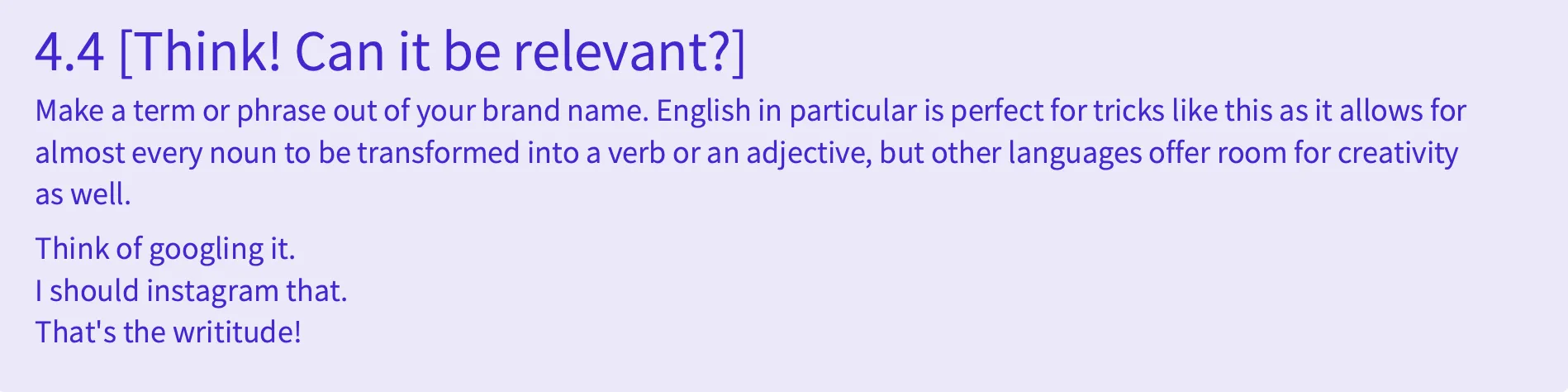

4.5. Differences in [your Company’s] tone of voice for different target audience personas

Now that your [your Company’s] Tone of voice has been lined out and explained in detail through multiple examples, let’s outline the possible differences in tone when you’re communicating with different segments of your audience.

Often these variations match the diversities in products or services you’re offering to different customer segments, but sometimes there may be several sub-audiences for one product or service.

(Describe the differences in tone of communication with different target audience personas — on the level of content & structure, style and grammar.)

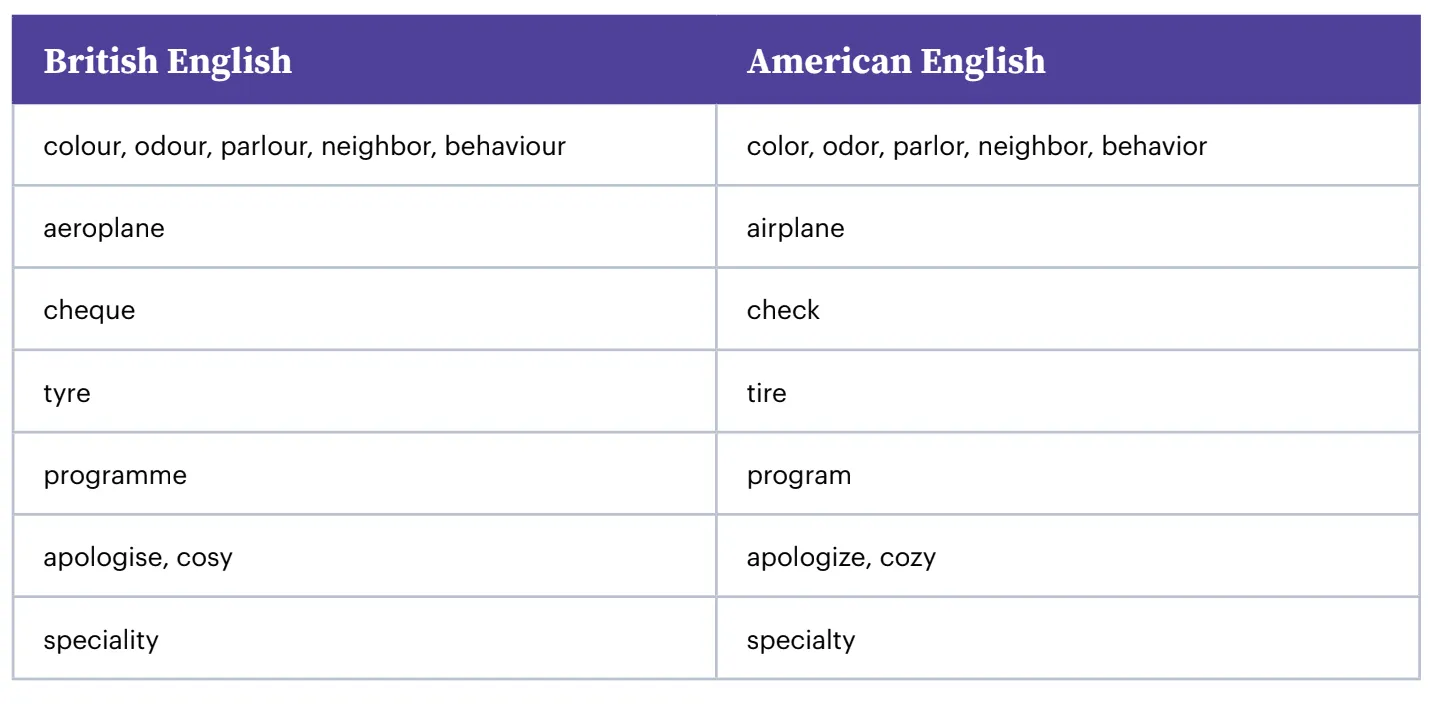

4.6. English vs American English

We choose to follow the rules of [your Company’s choice] English. So [your Company’s choice is American English, for example], it’s sneakers (not trainers), french fries (not chips), a cookie (not a biscuit) and subway (not underground or tube). But most importantly, pay attention to the spelling of similar words like these:

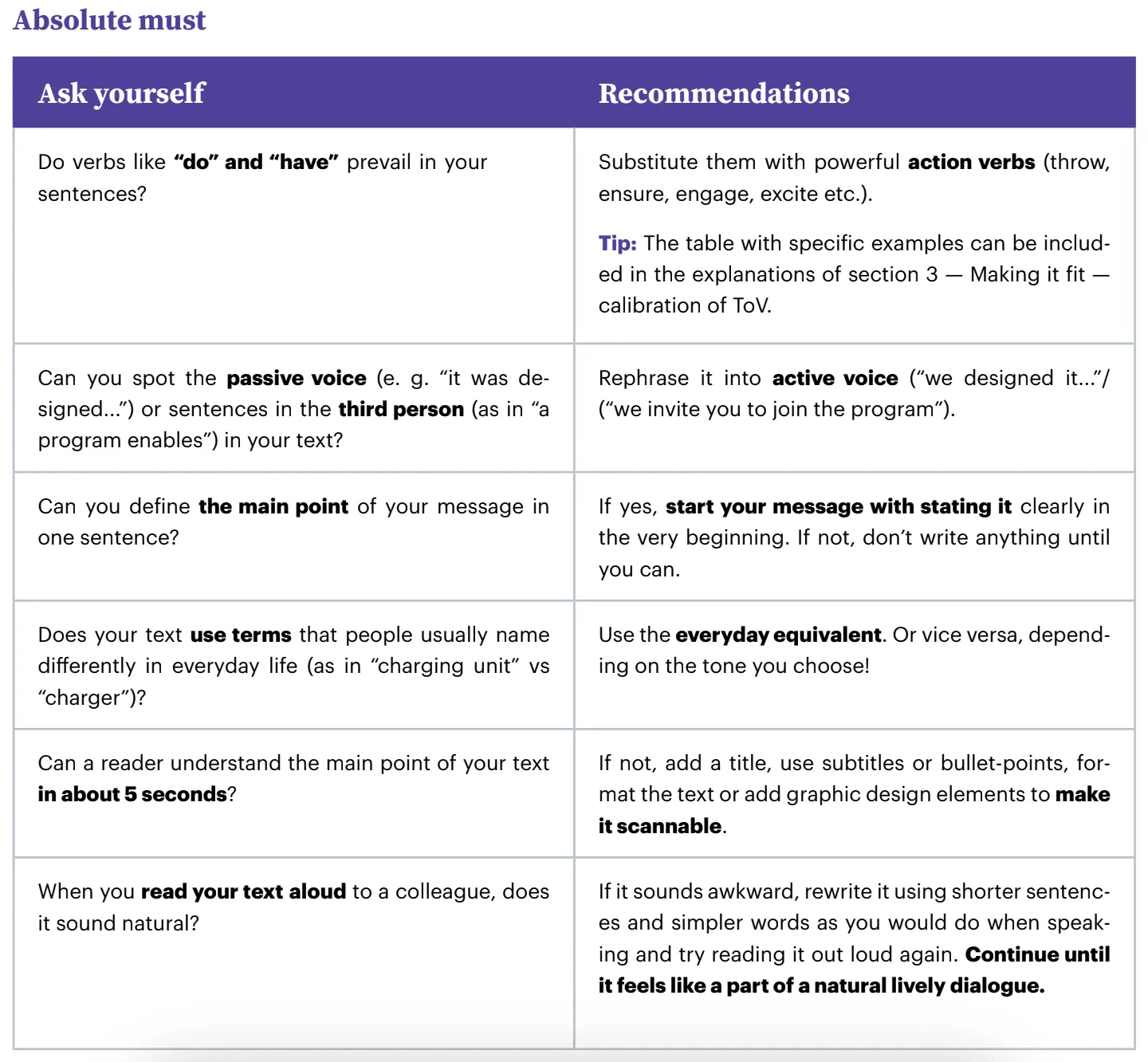

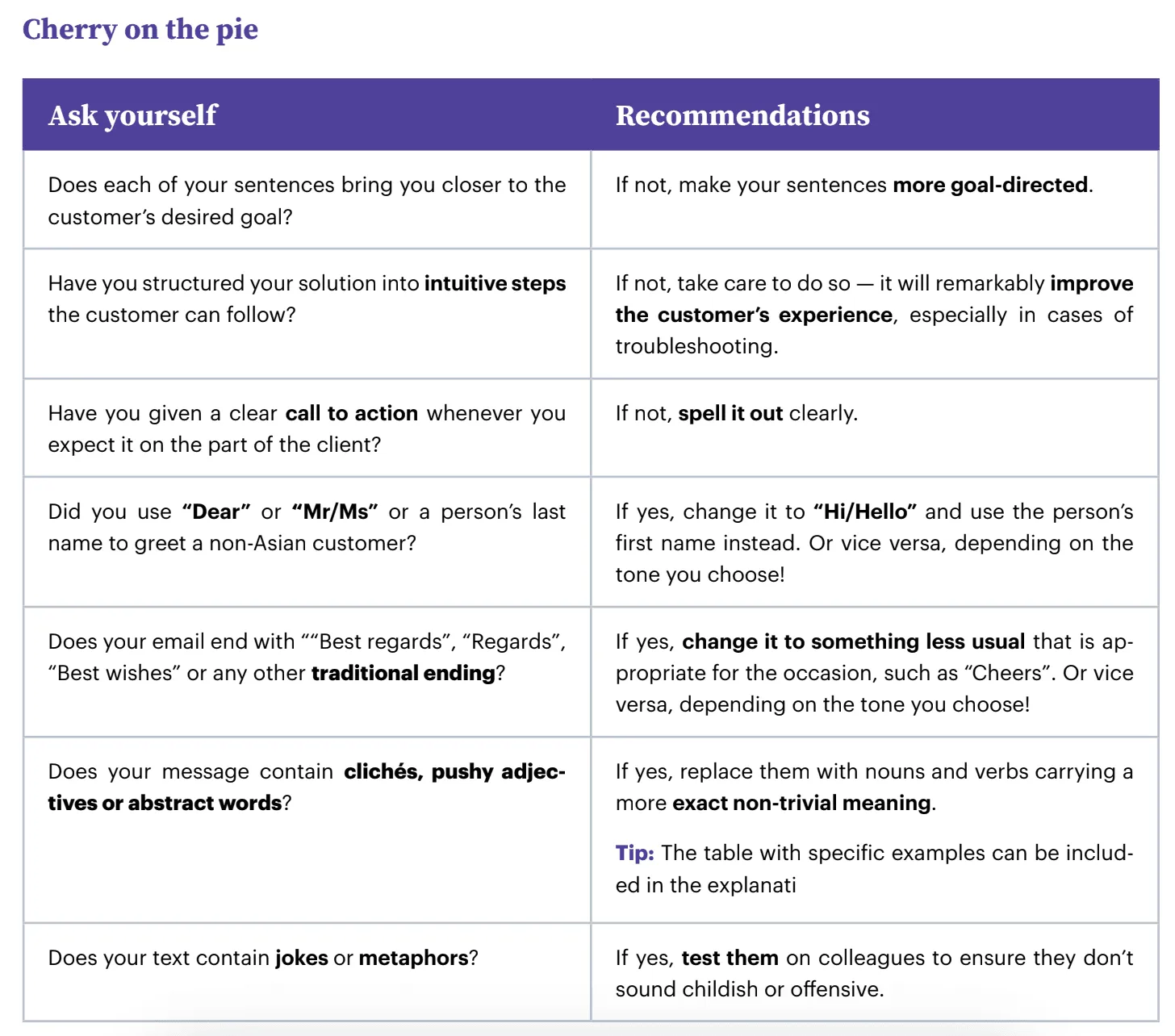

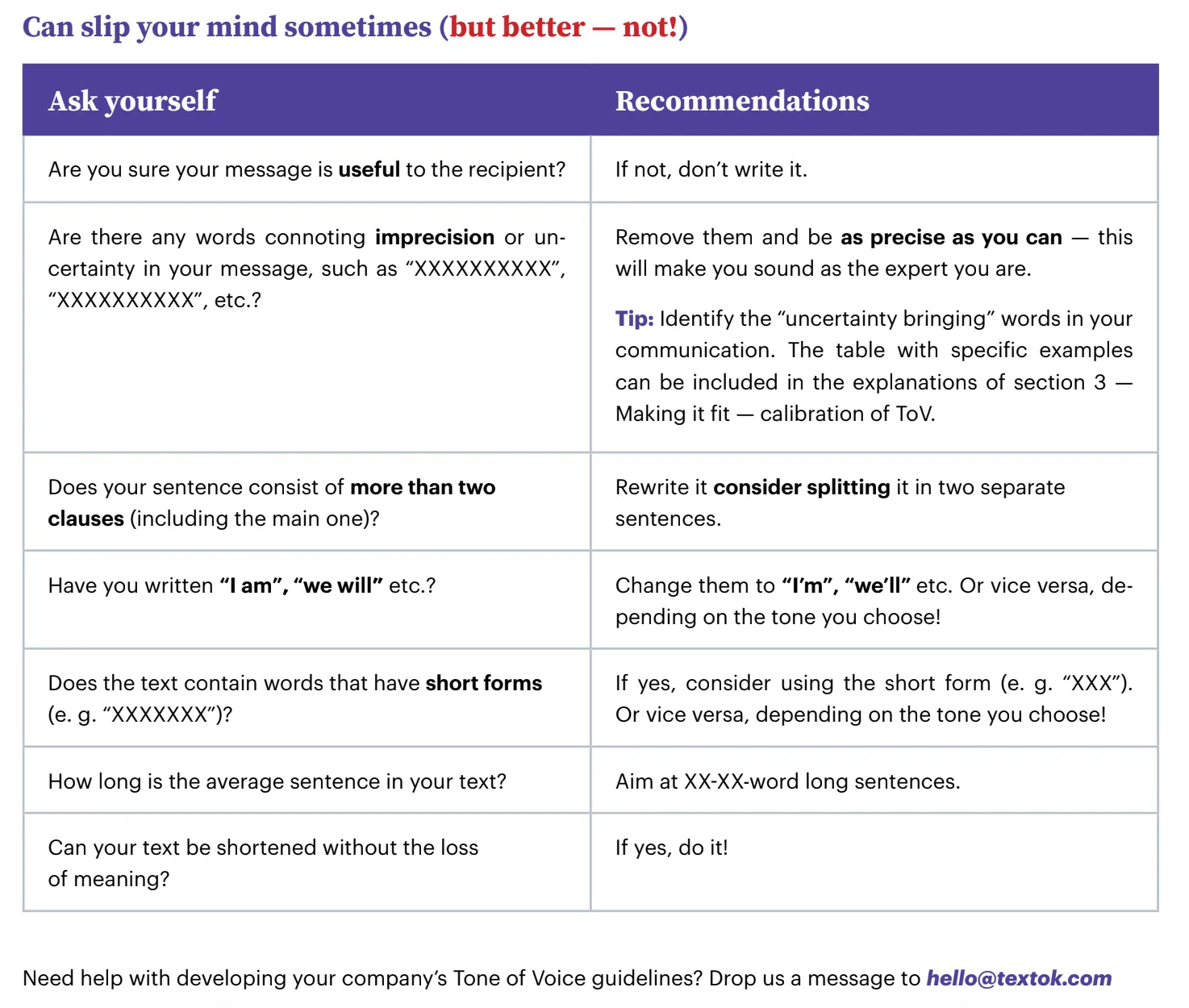

5. Summary & checklist

These control questions are the quickest way to check, if the text you are looking at (whether written by yourself, a colleague in the next room or someone else a long time ago, a copywriting or PR agency or a freelancer) is consistent with [your Company’s] tone of voice.

They also offer advice on re-writing a text to achieve the best result. The arguments behind these requirements are set out in detail in Parts 2 and 3 of these guidelines.

(We created these recommendations following the examples in this ToV guidelines template document as well as best practice — use your own control questions and answers by following what’s important to your own company’s brand tone!)

Need help with developing your company’s tone of voice guidelines? Drop us a message to [email protected]!